My Personal Roots

I grew up in the 1980s in a Southern Baptist church, home, and community, but I was not exposed to creationism until my sophomore year of high school. And it was not at church. It was in my AP Biology 2 class at a public school. Our teacher had announced that, to avoid arguments about evolution, we would just be skipping that topic – you know, a topic essential to understanding biology. However, a few students saw an opportunity and brought creationist literature from home. They talked about them during breaks, loaned them out, and encouraged us to go to events and book studies at their churches.

Honestly, the most appealing draw was not the books themselves, but that the students promoting these ideas happened to be a year older than me and people I looked up to. They were bright and clever; they excelled at speech and debate and had been mentors on the debate team. So I visited one of their churches once, and I read the books. And while I never became a young-earther, I played with the idea and wasted time and money investigating something that should never have been given my serious consideration. I had similar experiences with other hot button issues. And while I managed to avoid getting caught over the long term, I cannot say they did not influence me, and I have my own personal collection of embarrassing moments. I did not finally and fully break from that tradition until 2007, when I was 30 years old. Looking back, that feels impossible, especially in contrast to how deep and wonderful my life has become. It is strange to remember how compelling some of those arguments and conspiracies felt to me back then. And that has inspired my curiosity. What was it that made me susceptible to those traps? And what enabled me to get free?

Our Evolutionary Roots

By and large, we humans like to be right. We like to believe we have it all figured out. In general, it feels better to us if others are wrong. We can also reinforce our beliefs, or comfort ourselves in uncertainty, by convincing others to agree with us. Moreover, we tend to identify with our views and defend them, and it feels embarrassing to realize we’ve fallen prey to a scam. We also like to belong, so we may embrace certain views, even conspiracy theories, as an expression of loyalty to our group. These kinds of factors have pushed our evolution as a species in the direction of preserving cognitive biases. After all, in the survival of a species, adaptability is often prioritized over truth.

In 2009, a team of researchers led by Martie Haselton (with Gregory Bryant, Andreas Wilke, David Frederick, Andrew Galperin, Willem Frankenhuis, and Tyler Moore) explored “Adaptive Rationality: An Evolutionary Perspective on Cognitive Bias.” They pointed out that, while we often like to think of ourselves as uniquely “gifted with a propensity to uncover and strive for truth, or some version of it,” the reality is that natural selection may favor sacrificing “costly truth-seeking in favor of fast approximations.” This includes our social lives:

“The conviction that one's own social group is somehow special, or even better than other comparable groups …, or the belief that one's current partner is the most amazing and irreplaceable person in the world … could lead the believer to behave in ways that might contribute to his or her social success … .” (https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1053&context=psychology_articles )

This is not very flattering, which becomes another reason that humans try to avoid looking at it honestly. I see that looking back at my own childhood denomination, with our insistence on being the best and most faithful of all Christian traditions. Any evidence that pointed otherwise was a threat, and treated as such, which hurt people like me but helped keep alive what would surely have been a failing denomination. Similarly, there’s nothing romantic about realizing your belief that your sexual partner is the most amazing person in the world is one of the ways our brains convince our species to reproduce. Realizing this may help us cultivate healthier, longer-lasting relationships, but it can come as a shock in a society built around these romantic images. And this is part of the point: the capacity for these beliefs persists because, at least in some way, they have served some psychosocial purpose. Sometimes, poor reasoning, fallible assumptions, and false beliefs are wrong about reality, but can still be right when it comes to evolutionary success. There are limits to this, and no organism or species can thrive while always making poor judgments or false inferences. But, as Haselton’s team explained, “this is quite different from claiming that the brain essentially strives for truth, as if it were evolutionarily optimized for arriving at truthful judgments and logical inference.” (ibid) No, these are things we have to do on purpose, intentionally learning and practicing those skills.

From Hostile Coalitions to Conspiracy Theories

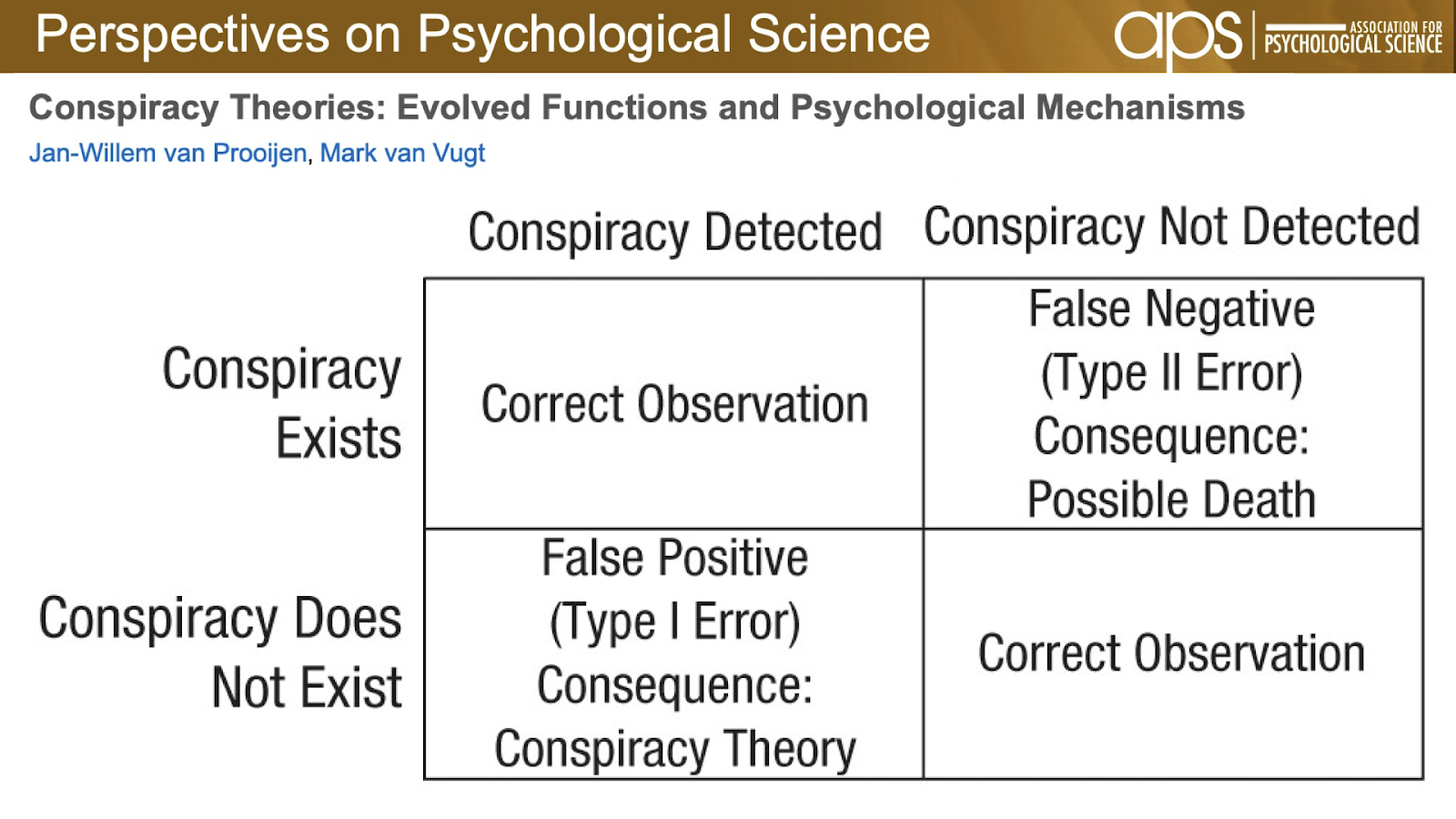

To better understand this, researchers have turned their attention to the role of cooperative alliances and hostile coalitions in human evolution. If you are familiar with humanity’s negativity bias, you’ll notice some similarities in this table from a 2018 study by Jan-Willem van Prooijen and Mark van Vugt, “Conspiracy Theories: Evolved Functions and Psychological Mechanisms”:

In terms of human evolution, the cost of a false positive – to believe in a conspiracy that does not exist – is much lower than the cost of a false negative – to not believe in a conspiracy that turns out to be true. In the former, any of our conspiracy-loving ancestors were probably unhappier, but they managed to stay alive. In the latter case, a failure to act on an actual threat could easily result in death. Van Prooijen and van Vugt explained that both the tendency to form cooperative alliances, and the ability to recognize when others when others are forming alliances that may be hostile, has been a common human characteristic for over two million years:

In discussions about our negativity bias, it’s common to observe that “Evolution doesn’t care if you’re happy.” When it comes to hostile coalitions and conspiracies, a similar idea could be expressed: “Evolution doesn’t care if you’re right.” In the end, truth often took a back seat to whatever helped an organism survive long enough to successfully reproduce. And that means we’ve inherited a vulnerability to believe the outrageous, outlandish, and the dangerous – especially if we believe it will help our in-group succeed.“Given the realistic dangers of hostile coalitions in an ancestral environment, along with the life-saving functionality of detecting conspiracies before they strike, conspiracy beliefs are likely to have been adaptive among ancient hunter-gatherers.” (ibid)

Doing the Math

As disturbing as this may be, it helps us make sense of the some of the contradictions inside and around us. We humans love to think of ourselves as rational, all the while being susceptible to a host of irrational behaviors. And we like to think of ourselves as exceptions to the rule. If you disagree with me, there is always the temptation for me to fall back to the assumption that your view is wrong simply because you thought of it, instead of me. You can glimpse the convincing un-logic lurking here: 1) I am a critical thinker; 2) I believe this statement; 3) therefore, I arrived at this conclusion through critical thinking.

Especially over the last decade, this tendency has repeated itself in conversations with and studies about conspiracy theorists. I watched as people toyed with believing, or even aggressively defending, the most outlandish and dangerous beliefs while asserting that their belief in a conspiracy theory was the result of their own critical thinking. With ignorance armed with such overconfidence, those who went along with the scientific consensus were just “sheeple,” while the true defenders of rationality and liberty were those brave enough to believe the conspiracy. In fact, if I brought evidence from scientists or other experts into the conversation, they simply took this as confirmation of how the establishment was hiding the truth that they had discovered.

In 2016, Jaron Harambam and Stef Aupers studied a similar phenomenon in the Netherlands (“‘I Am Not a Conspiracy Theorist’: Relational Identifications in the Dutch Conspiracy Milieu”). They found that people tried to “actively resist their stigmatization as ‘conspiracy theorists’ by distinguishing themselves from the mainstream as ‘critical freethinkers’” and then attempt to “reclaim rationality” by applying the conspiracy theorist labels to others. This all felt disturbingly familiar, and I realized it was eerily similar to my own experiences in conservative religious communities. The drift among evangelical Christians toward embracing conspiracy theories, for example, has not been hidden. This has been a very public strategy for decades, capitalizing on our biases so they could amass a powerful empire of pseudo-scientific institutions, think-tanks, and true believers.

You can see it clearly in my AP Biology II course. Students brought in books that were published by presses specifically created to print and distribute anti-evolution materials. Their authors, like the creationist movement they belonged to, insisted that their views should be given the same weight and authority that peer-reviewed research was given. They further insisted that members of the scientific community were actively persecuting creationists in order to suppress the truth. Linking their anti-evolutionary teachings to their conservative theologies, they upped the stakes of rejecting their conspiratorial claims. The version I most often heard was that the reason scientists rejected creationist ideas was because they rejected God. The implication was that if I accepted the fact of evolution, I would also be rejecting God.

If you have already accepted that kind of religious worldview, the math is very easy here. The risk of being wrong about evolution is inconsequential compared to the risk of being wrong about God. In the evolution versus creationism conspiracy, the false positive (you believed in creationism but evolution turned out to be true) is a risk worth taking, because you have to do everything you can to avoid the possibility of the false negative (you rejected creationism and, in turn, rejected God and, by extension, salvation from being tortured forever in hell). And here is where the anti-evolution claims veered toward conspiracy theories. Our in-group (the true believers, faithful to God) were being attacked and corrupted by an out-group (the evil scientists who rejected God and came up with evolution as a way of deceiving the masses).

Repeating the Pattern

This type of choice has been repeated for other issues, including issues related to abortion and reproductive justice, gender and sexuality, and anti-vaccination claims. For decades, people have been taught to distrust scientists, medical care providers, and public health officials, in favor of trusting these pseudoscientific institutions and think-tanks. And one essential factor in their success is that they appeal to that in-group identity, that human tendency to form and then to protect their alliance against the enemies they perceive as hostile coalitions. For every one of those issues, someone, usually a marginalized group, has been identified and made an enemy. The claims are easier to swallow, it turns out, when you can do so out of a protective instinct to save your group.

It should not come as a surprise, either, that there is a lot of overlap in these conspiracy theory movements. For example, much of the outrage over Critical Race Theory was sparked when someone leaked materials from a training in my home town's public schools to the Discovery Institute. For those of you lucky enough to be unfamiliar, the Discovery Institute is one of those pseudoscientific think-tanks that has specialized in promoting intelligent design and opposing instruction about evolution. They were famous for the slogan, “Teach the Controversy,” a classic attempt to make their claims seem legitimate by creating a debate where no debate actually existed.

What would such a place have to do with Critical Race Theory? What they have in common is their alliance against those they’ve deemed as hostile coalitions, those “others” they believe threaten their way of life. Fellows of the Discovery Institute have been branching out, embracing more conspiracies along the way, from denying climate change to criticizing mask mandates during the pandemic to promoting the lie that the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump. And it is no accident that a former employee at the Discovery Institute became a spokesperson for opposing Critical Race Theory. A group that feels threatened is more vulnerable to promoting conspiracy theories, and its members have heightened reasons to risk believing.

Those decades of hard work to build alliances and identify hostile coalitions has made our society fertile ground for conspiracy theories. And while the capacity to believe in conspiracies may have been adaptive for our ancestors, our situation has changed in many ways, making conspiracy theories increasingly dangerous and harmful. In a time when we need to be mobilizing all our attention and efforts to address the real and urgent problems we are facing, such as climate change, masses of us are instead busily obsessed with disinformation and conspiracies, from the normalization of Christian nationalism, signaled by folks like Marjorie Taylor Greene, to the whitewashing of our history in deference to fragile pseudo-patriotic egos, to the politicization of life-saving vaccinations, and more. Especially when adopted on such a large scale, this is another disastrous consequence of conspiracy theories: they distract us from the dangers that actually exist.

A Way Forward?

I understand this is gloomy, but it is also hopeful. Understanding some of the reasons why our society has been spiraling around so many conspiracy theories helps us become more strategic about how to work for change. Many of the responses to conspiracy theories that I’ve seen emphasize either 1) correcting the false assumptions and lies and 2) teaching critical thinking skills. I support both tactics, both personally and socially. All of us can take steps to be better informed, and picking up a book on critical thinking is a great way to take care for the mind. We can also support policies, such as holding social media companies accountable for disinformation, or supporting teaching critical thinking in our education system. All of these are worthwhile and important.

But the emerging research on conspiracy theories also reveals that his is not a wound we can heal mainly by winning arguments. Not even having solid evidence is enough. Because the roots of our vulnerabilities are in the social and psychological factors, those factors must be addressed. For example, a 2021 study of conspiracy theories related to covid-19 by Tianru Guan, Tianyang Liu, and Randong Yuan showed that human-centered methods were most effective at reducing acceptance of conspiracy theories. Two examples stood out. The first focused on “decoding the myth of conspiracy theory,” rather than tackling the conspiracy head-on. This meant uncovering how conspiracy theories work, such as the psychological drive to seek certainty during particularly chaotic and stressful times. The focus is on helping people:

“understand their own cognitive vulnerability in the face of conspiracy narratives [more] than criticizing the processes of media content production. … The ‘decoding’ approach can clarify the nonsensical status of these false propositions, showing that they only ‘make sense’ as a result of misguided use of language and a biased cognitive process of information-processing.” (“Facing disinformation: Five methods to counter conspiracy theories amid the Covid-19 pandemic”)

Practically speaking, this means creating and sharing resources about how and why humans are susceptible to conspiracy theories.

Second, the study affirmed the effectiveness of “reimagining intergroup relations.” We need to center and protect marginalized communities, especially ones that become the focus of conspiracy theories. Though they are always at risk, those risks are heightened when they are made the face of the enemy. Remember that conspiracy theories require believing that a secret, hostile coalition is planning to harm you. There is probably not a better argument against a conspiracy theory in the long term than to demonstrate that a dehumanized out-group is a vibrant, essential part of our society, instead of a threat. There are policies to pursue here, and we talk about these social justice issues a lot. But this is also liberating at a personal level. Instead of getting caught in an endless loop of opposing disinformation, we can listen to marginalized voices and learn to live in solidarity. Instead of getting lost in arguments, we can make friends. And instead of standing by helplessly while conspiracy theorists run amok, we can cultivate the types of communities where not only are conspiracy theories less likely, but where we actually enjoy living.