For years now, we’ve been discussing different aspects how to manage broken relationships, especially relationships strained by the increasing polarization of American society. More and more people speak with me about feelings of isolation and loneliness. Even before the pandemic, more than 40% of Americans reported feeling that their relationships weren’t meaningful, and 20% said that they “rarely or never feel close to people”. (https://www.welcomingpath.com/2019/09/loneliness-listening-and-gift-of.html )

Arriving at Estrangement

These feelings of disconnection and isolation include our family relationships. In 2020, Karl Pillemer of Cornell University documented the results of a large-scale survey on estrangement. The study found that 27% of respondents shared they had completely “cut off contact” with at least one family member. (https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2020/09/pillemer-family-estrangement-problem-hiding-plain-sight ) And since this is information not everyone is ready or willing to share, the actual number is probably even higher. We can add to this tally those relationships that are strained, but not yet broken. When we pause to acknowledge it in this way, we glimpse the enormity of pain and stress that we are carrying around. As Pillemer pointed out, this “rejection and powerlessness” has a cumulative and harmful impact on our well-being and the well-being of our communities, weighing us with both grief and a “sense of incompleteness”. The weight is a chronic stressor, especially when it includes family relationships where we experienced bonding and attachment in the past. (ibid)

This kind of estrangement is also the slow fruit of long conflicts and destructive relationship patterns. Abuse, whether emotional, verbal, physical, sexual, or a combination, is at the top of the list of common causes. These are deep wounds. Divorce is also a common influence, with various causes, from feeling the pressure to choose between feuding parents to finding new conflicts in blended families. But it is also increasingly common to find that conflicting values are behind a clash. In one study, “value-based disagreements” played a role in more than a third of rifts between mothers and children. These differences in values usually relate to issues of gender, sexuality, religion, and politics. As we well know, these differences have been amplified by the polarization of most of life in recent years, fueled by popular political candidates and cultural and religious leaders stoking xenophobia and conspiracy theories. (https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20211201-family-estrangement-why-adults-are-cutting-off-their-parents )

Distrust Becomes the Default

Some people have been surprised by this shift, but the reality is that we have been creating these conditions for a very long time. My own estrangement from my extended family has been twofold. The value-based disagreements are certainly present. It became very difficult to attend family gatherings with someone, for example, who openly carried a firearm and held racist, misogynist, homophobic, and transphobic views. There was no way for me to realistically feel or be safe in that situation.

But underneath the values-based rifts was a deeper unwillingness or inability for our family members to honestly engage with harmful patterns of abuse and dysfunction. I have always maintained that I am willing to do the work to honestly engage with, heal from, and transform those patterns. But I am not willing to pretend that they do not exist and expose myself and my loved ones to further harm.

This makes me one of those statistics that Pillemer lamented, estranged from several extended family members for many years. I’ve also connected with many people with similar experiences. Very often, we’ve lived through a merging of unhealthy family and religious experiences and cultures. And these experiences connect deeply with issues of trust.

Growing up in communities that tolerated abuse and dysfunction, the lesson that many of us learned was doubly harmful. On the one hand, I felt pressure to trust everyone, at least everyone in our family or church community. Distrust was a sign that something was wrong with me, because the people in our circles were good by definition. We weren’t encouraged to heal and transform unhealthy relationships, because that would require acknowledging that something was wrong in the first place. This was generally not allowed. Especially in our conservative church culture, problems were only allowed in the past tense. You could sometimes share the problems you were facing, if they weren’t too scandalous, but only after you had resolved them. This became your chance to give testimony about how God had changed your life. But we didn’t really ask for help for relational problems, especially not publicly. Instead, we quietly hid them away – perhaps out of helplessness or shame, but always to our collective harm. In such an environment, vocalizing distrust came perilously close to unmasking how broken our relationships often were, and that was too big of a risk.

In such a culture, though, trust became increasingly impossible, especially for any of us who had suffered abuse. The reality was that, while we felt pressure to trust everyone, we often didn’t trust anyone. How could we, especially when the people who hurt us were also the people society insisted that we should - and had - to trust? Over the years, I found my own experiences mirrored in the stories that countless people have shared with me. How do we trust, when we so often were harmed by the very people we were taught would protect and care for us? Over time, we learned that the way to stay safe was to assume the opposite about people. Distrust becomes the default.

A Spectrum of Trust

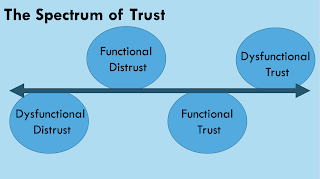

So this is where I find it necessary to start. I grew up learning that trust was an either/or proposition. Through decades of tending to both my own healing and supporting others, I have learned that trust is more like a spectrum. At the far ends we have dysfunctional or unhealthy patterns of trusting and distrusting. Dysfunctional trust is the tendency to trust when we should be exercising boundaries and caution. At the extreme, dysfunctional trust puts us in a position to be harmed, especially repeatedly. We stay in unsafe and unhealthy relationships and groups too long. We also risk normalizing those destructive relational patterns, to the point that we tolerate, protect, and even promote them.

On the flip side, dysfunctional distrust is the tendency to distrust, no matter what. It often arises out of a legitimate need for self-protection; we refuse to be harmed again. But we do this in a way that leads to isolation and even paranoia. We resist forming any relationships at all because the risk of that kind of connection is too great. So we avoid cultivating safe and healthy relationships. This feels like a reasonable cost when compared with the cost of getting hurt again. And it often feels like a reasonable cost, even if we are desperately in need of community and connection.

Between these extremes we find varying degrees of trust and distrust, and in the middle is the sweet spot. This is where we find trust that is healthy and relationships that are supportive and caring. But this is also where we find distrust that is healthy, where we are honoring the process of building (or rebuilding) trust. Healthy relationships cannot be coerced. And if you take one thing away from these reflections, my guess is that the most helpful idea for most people is simply this: distrust can be healthy. It isn’t automatically or inevitably healthy, no more than trust is automatically or inevitably healthy. But distrust is an important part of how we grow into strong, healthy communities. This is part of how we honor our bodies and needs, get in touch with our boundaries and limitations, practice compassionate communication, and learn how to give and receive care without hurting one another.

Learning How to (Dis)Trust

We practice these skills internally, inside ourselves, and with each other, in our personal relationships and in our communities and organizations. Cultivating a culture of trust helps all of this happen. Time and again in conflict work, I’ve noticed that, when parties in a conflict can’t trust one another, they may be able to trust a mediator. This is why we spend a significant amount of time in pre-meetings with each party in a conflict, building rapport. That trust can then become a bridge for the parties to meet each other again. Similarly, in a community or organization that takes the time to cultivate a culture of trust, we have a much better chance that conflict won’t become overwhelming. We have a better chance of resolving a difference before harm is done. We have a better chance of healing when there is harm.

On the flipside, it’s much more challenging to address a problem or conflict when we don’t feel and aren’t safe. This isn’t easy work, and the reality is that some relationships are not safe to continue in any form. Single, traumatic incidents can destroy trust in a moment. But distrust can also emerge out of the accumulation of unhealthy relationship patterns. Especially in the latter case, the situation may gradually get worse and take years to recognize an unhealthy pattern. In my experience, this often means that we are prone to staying in unhealthy relationships for too long. Unfortunately, these aren’t usually situations we are prepared to explore, so we often work through questions, such as:

- When do I feel comfortable addressing problems?

- What practices and values help me feel both safe and empowered to work through a conflict?

- When am I least likely to feel that safety and power?

- How do I recognize when trust or distrust has become unhealthy?

- What tools and skills have been most helpful, and what tools and skills are still needed?

Moving toward Wellbeing

Getting practice like this in our personal lives also gives us insight into how can we create environments and communities where it is safe to heal from dysfunctional forms of trust and distrust, and where we can learn to practice functional trust and distrust. Going back to the Cornell research on estrangement and reconciliation, Pillemer shared that most instances of healing involved: 1) moving from a focus on the past to a focus on the present, 2) envisioning what a future relationship might be like, and 3) shifting a focus from trying to change the other person to “adopting more realistic expectations” about what was possible. (op cit)

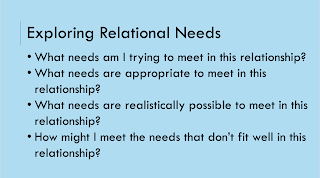

I would further clarify that the shift from past to present is one where we move from adjudicating the past (what really happened, who is to blame, who is right) to healing in the present (how did what happen change us, what wounds still need to be healed, how can we cooperate in this healing). We can then explore that boundary between what is possible and what is healthy:

- What needs am I trying to meet in this relationship?

- What needs are appropriate to meet in this relationship?

- What needs are realistically possible to meet in this relationship?

- How might I meet the needs that don’t fit well in this relationship?

When you think about it in these terms, you can recognize that we are already experts in navigating trust and distrust. For example, you can trust me for a whole lot of things, but you really shouldn’t trust me with, say, repairing your car. That won’t go well for any of us! We are constantly making decisions like this, and we can tap into that wisdom to help us navigate more challenging relationships. I find this especially helpful in discerning how to relate with someone with whom I have a significant difference of values. Sometimes the answer is still, “there isn’t a safe way,” but, even then, the process is still valuable for me.

Finally, another aspect is the importance of centering the voices and needs of marginalized people. Oppression is the most severe and cruel normalization of harm, and it destroys the possibility of trust. This means that prioritizing justice and equity are part of the restoration of trust and the healing of both people and society. Similarly, the wellbeing of marginalized and oppressed people is the measure of the health of a society. Any work we are doing that ignores this dynamic will ultimately undermine our efforts, whatever our intentions.

And this is important, because our vision of justice and equity is a shared vision; it is about learning to live together without harming one another. It is about being able to heal from our hypervigilance because we feel and are safe. It is about being able to relax and laugh and enjoy life. Social justice work is relational work, within ourselves, with each other, and in our communities and organizations. Making room for us to understand and practice the spectrum of trust supports this vital, healing, life-giving work. So thank you to everyone who has supported my own healing, and the healing of others. Thank you to everyone who has shared in this work - caring for our most painful wounds with compassion, and creating together communities where we can finally trust ourselves and one another with the fragile, precious, and wonderful joys of life.